Throughout much of the 1800's, the east side of the Eleventh Ward (the official designation of the area we call the East Village) was an important center of shipbuilding. In 1824, a group of shipbuilders came together as the New York Dry Dock Company to construct an inclined railway at the foot of East 10th Street to pull ships from the water for repair. By 1844 there were shipyards extending along the East River from Grand Street to 12th Street.

The area became known as the "Dry Dock" district, or in some texts, simply "Dry Dock". (A dry dock is a large drainable basin used for building and/or repairing ships.) Dry Dock Street was located adjacent to the New York Dry Dock Company's facility.

1840: Detail from the Chapman and Hall map. This is the earliest map I found that includes Dry Dock Street (between Avenues C and D and 10th to 13th Streets), as well as the labeled "Dry Dock". Note the extension of Lewis Street (east of Avenue D), the remnant of which is today's Lillian Wald Dr. Also note the grayed areas which seem to indicate developed areas of the street grid--much of the area directly surrounding Tompkins Square remains undeveloped.

Rumsey Collection

Among the notable shipbuilders of the era was William H. Webb, who built 133 ships (ranging from clippers to steamships) between 1840 and 1865 from his shipyard between 5th and 7th Streets.

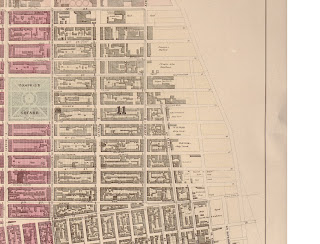

1867: Detail from the remarkable Dripps map. Dry Dock street has been trimmed back to 12th Street, and the William Webb shipyards are clearly marked. In contrast with the Chapman and Hall map above, the entire ward has been developed. Be sure to download the full-resolution version of this map!

Library of Congress

The area became the home for thousands of shipyard workers and their families. In 1921, Justice L.A. Giegerich recalled his childhood in the Eleventh Ward of the 1860's:

Neat brick dwelling houses containing at most two families occupied the greater portion of the area lying between Third and Ninth streets and Avenue C and the East River and there were also many such houses in other parts of the ward.The opportunities provided by the booming shipyards made the area a common landing point for Irish immigrants escaping the famine between 1845 and 1851. Plans were made for a Catholic church to serve this community, and in September 1848, the cornerstone was laid for St. Brigid's (named for the patron saint of boatmen). Designed by Patrick Keely, a noted designer of churches, the building on the southeast corner of Avenue B and 8th Street was dedicated in December 1849.

Valentine's Manual of Old New York, 1921 Edition

A view of St. Brigid's, c. 1928, looking across Avenue B from Tompkins Square Park.

NYPL Digital Gallery

Detail from the 1867 Dripps map showing St. Brigid's (labeled R.Ch.) on the corner of Avenue B and 8th Street.

Library of CongressA recent view of St. Brigid's (from the Save St. Brigid web site). The steeples were removed in 1962 due to structural concerns.

| St. Brigid's recently survived a demolition scare and today is undergoing a massive restoration effort. To see how you can help save this enormously historic structure, please visit Save St. Brigid. |

Read more about the early history of St. Brigid's in The Catholic churches of New York City, with sketches of their history and lives of the present pastors (1878).

Extra credit: Find St. Brigid's in this extraordinary 1913 photo (hat tip to Shorpy's).

Today, Dry Dock Street remains, although its name was changed to Szold Place in 1951 to honor Henrietta Szold, founder of the women's Zionist organization, Hadassah. The adjacent Dry Dock Playground & Pool is the only neighborhood reminder I could find of this once thriving industry.

An Interesting Artifact: Dry Dock Savings Institution

In 1848, the Dry Dock Savings Institution was incorporated to serve the growing population of Dry Dock. There was no other bank east of the Bowery at that time, so the bank grew quickly after opening in a two-story brick building on East 4th Street, just west of Avenue C. The bank merged with Dollar Savings Bank in 1983, and in 1992, Dollar Dry Dock failed due to losses from real estate loans.

The gothic Dry Dock Savings Institution building at Bowery and 3rd Street, designed by Leopold Eidlitz and erected in 1875 (demolished) was actually the bank's third location.

NYPL Digital Gallery

NYPL Digital Gallery

Other Maps

1832: Detail from the Burr map of the Eleventh Ward. This early map does not yet show the dry dock, or even Tompkins Square (which opened in 1834). Also note how severely the shoreline encroaches as far west as Avenue B north of 10th Street.

1832: Detail from the Burr map of the Eleventh Ward. This early map does not yet show the dry dock, or even Tompkins Square (which opened in 1834). Also note how severely the shoreline encroaches as far west as Avenue B north of 10th Street.

1846: Detail from the Mitchell map. The Dry Dock and Dry Dock Street are clearly marked.

Rumsey Collection

Rumsey Collection

Notable References and Original Sources

- History of New York Ship Yards, Morrison, 1909

- Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Burrows and Wallace, 2000

- Century of American Savings Banks, Manning, 1917

- Catholics in New York: Society, Culture, and Politics, 1808-1946

- THE DOOM NEAR OF OLD "POLITICAL ROW"; New Tenement Invasion in the Famous East Seventh Street (New York Times, May 11, 1902)

- Valentine's Manual of Old New York, 1921 Edition. In his oft-reprinted article "REMINISCENCES OF THE OLD ELEVENTH WARD," Justice L. A. Giegerich (New York Supreme Court) recounts his childhood in the Eleventh Ward and its transition in the prior 60 years from single- and two-family homes to dense tenements. (He also references the above Times article.)

- William H. Webb's obituary

WILLIAM H. WEBB DEAD.; The Well-Known Authority on Marine Architecture and Former Ship Builder Succumbs Suddenly (New York Times, October 31, 1899)